| Finally,

encouraged by the Confederate president Jefferson Davis to do something,

Johnston made a move. Feeling that the right wing of McClellan's forces,

straddling the Chickahominy River was the weakness of the Union force, Johnston

decided to attack. Pettigrew's brigade was placed in Smith's Division,

temporarily under the command of William Henry Chase Whiting. Gustavas Woodson

Smith would lead the left wing of the Confederate attack.

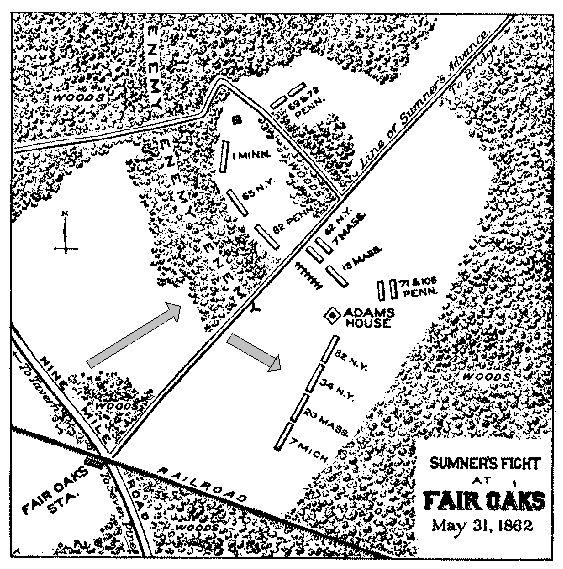

courtesy General Officers of the Civil War Mismanaged from the very start, the Confederate attack would initially push the Union back and exploit its weakness', but Union reinforcements brought the two day battle to a draw at best. The battle began at 1 pm on May 31st, but it would be late in the day before the 35th Georgia would go into action. It would be the first time the men of the 35th would "see the elephant", as rookies called their first combat then, and before dusk fell, they paid heavy for the experience. Whiting's attack on Gen Darius Nash Couch's Union command was to protect Longstreet's command, most of which was stuck on Nine Mile Road, and to keep Couch from reinforcing the Union forces under attack south of the river. Holding the right wing of this sudden offensive movement, the 35th under Pettigrew, advanced under a murderous fire from Capt James Brady's 6 gun Napoleon battery. Determined to take the Union guns, Whiting again called for a unified attack upon the Union line at about 4:30 pm. Crouch's strained forces were being reinforced with additional troops and Whiting knew he was losing his advantage. Union General John Sedgwick had marched his forces from the rear at the first sounds of battle, across the flooded Chickahominy and had just arrived, quickly moving his fresh troops into line.

courtesy General Officers of the Civil War To the left of the artillery battery he placed the 82nd New York and the 34th New York (nicknamed the "Herkimer Regiment. His other regiment's were moved to the right of the guns to support Couch's battered men. It was here that the 35th Georgia would charge, attacking the 34th New York. Yet, even after the Georgian's had emerged from the wood's and were attacking, more Union reinforcements were arriving. Under fire, the 20th Massachusetts (the "Harvard Regiment" under Col William Lee, West Point classmate and distant relative of Robert E Lee) and the 7th Michigan moved to the 34th New York's left and fired upon the advancing Georgian's.

Lt Henry Rope of the 20th Mass wrote "We again took the double quick step and ran through deep mud and pools of water toward the battle. The whole field in the rear of the line of firing was covered with dead; and wounded men were coming in in great numbers, some walking, some limping, some carried on stretchers and blankets, many with shattered limbs exposed and dripping with blood. In a moment we entered the fire. The noise was terrific, the balls whistled by us and the shells exploded over us and by our side; the whole scene dark with smoke and lit up by the streams of fire from our battery and from our Infantry in line on each side. We were carried to the left and formed in line, and then marched by the left flank and advanced to the front and opened fire. Our men behaved with the greatest steadiness and stood up and fired and did exactly what they were told. The necessary confusion was very great, and it was as much as all the Officers could do to give the commands and see to the men. We changed position 2 or 3 times under a hot fire. Donnelly and Chase of my company fell not 2 feet from me. The shell and balls seemed all round us, and yet few seemed to fall. We kept up this heavy firing for some time, when the enemy came out of the woods in front and made a grand attack on the battery. They were met by grape and canister and a tremendous fire of the Infantry." (From the Letters of Lt. Henry Ropes, 20th MA (ms, Boston, 1888) Rare Books and Manuscripts Dept., Boston Public Library Courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library)

Held in reserve behind three newly arrived Union cannon's under Lt Kirby, the 71st Pennsylvania watched the attack in awe. "Now there is a crush and a roaring as if the earth were rent asunder beneath our feet, and a flashing line of fire is succeeded by the blinding smoke of battle," recalled Captain Hill of Kirby's reply to the gray infantry. "The battery shakes the ground with its rapid discharges; the horses, terror-stricken by the sound, break loose and dash wildly to the rear." One of the Napoleon's broke its trail on its fourth discharge but quickly was replaced by two more of Kirby's pieces then arriving on the field. The Southern troops suffered under this withering fire."

Eventually, the Confederate's realized they faced overwhelming odds, and fell back. Behind them they left a wounded General Pettigrew. Also mortally wounded in this charge, fell Lt Colonel Bull of the 35th Georgia.

Realizing the best defense would be a strong offense, the Union Army decided to charge. As dusk fell over the battlefield, the Union left, the same men that Pettigrew's forces had just faced, now charged and the Confederate's withdrew from the woods in disorder.

Major Henry Abbott of the 20th Mass wrote "Then our whole line charged, the first half the distance in quick time, without cheering, except from old Sumner, who cheered us as we passed, the second half the way taking the double-quick with the loudest cheers we could get up" (Robert Garth Scott, ed., Fallen Leaves: The Civil War Letters of Major Henry Livermore Abbott Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1991) pp. 128-129)

Abbott continues - "Over the fence we went...It was now dark. We lay on our arms, on marshy ground; without blankets, officers being obliged to sit up, every body wet through as to his feet and trousers, & we had brought our blankets, but gave them all up to the wounded prisoners, of whom our regiment took a large number.... My company took 10 unwounded, & 11 wounded rebels prisoner in the woods…. Among the wounded, Brig. Gen. Pettigrew of SC & Lt. Col. Bull of the 35th Georgians. Pettigrew had given up all his side arms to some of his people before they ran away, in anticipation of being taken prisoner, & had only his watch, which of course I returned to him. Pettigrew will get well. Bull had his side arms, of which I allowed Corp. Summerhayes, his captor, to keep his pistol, an ordinary affair, while I kept his sword, an ordinary US infantry sword, which I intended to send as a present to you, but the Col., knowing [p.129] his family's address, wants me to send it to them, & as the poor fellow is dead, of course I can't hesitate to do any thing which would comfort his family. His scabbard, however, I found very convenient, as mine got broken in the battle and I threw it away. (Robert Garth Scott, ed., Fallen Leaves: The Civil War Letters of Major Henry Livermore Abbott (Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1991) pp. 128-129)

Oliver Wendall Holmes of the 20th Massachusetts wrote "It is singular what indifference one gets to look on the dead bodies in gray clothes which lie all around... As you go through the woods you stumble...perhaps tread on the swollen bodies, already fly blown and decaying, of men shot in the head back or bowels-Many of the wounds are terrible to look at.. [...] (Source- Anthony J. Milano, "Letters from the Harvard Regiments: The Story of the 2nd and 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiments from 1861 through 1863 as told by the letters of their Officers" (Civil War: The Magazine of the Civil War Society, Vol. XIII, pp. 23-24)

The next day, the 35th Georgia was quiet, as the battle resumed to the south, but forces north of the river held their respective positions. And so ended the 35th's baptism of fire, with deadly consequences. The battle had cost the 35th 23 of their men killed, and another 50 wounded. This was approximately 13% of its force. The major loss to the regiment was the death of Col Bull. One member of the regiment wrote Bull's father "The crushed and broken hearts that mourn the loss of the hero of the Thirty-fifth Georgia are not confined to your family circle." The wounded Pettigrew later wrote "If there was a better officer in the army than Colonel Bull, and one to whom the prospect of distinction in any department of life was brighter, I did not know him." (Henry W. Thomas, History of the Doles-Cook Brigade (1903; reprinted in facsimile by Morningside, 1988), Chapter II, History of the Fourth Georgia Regiment, Sketches of Regimental Officers, pp. 91-92.)

While the 35th had lost its second in command in the Battle of Seven Pines, or Fair Oaks, the brigade had lost its commander with the wounding and capture of Pettigrew. Of even more of concern to the Confederacy, was the wounding of Joseph Johnston, commander of the Confederate forces. With the Union Army stationed only miles from the Confederate capitol, Jefferson Davis moved quickly and placed a relatively unknown officer in command of the Confederate forces. His name, Robert E Lee. In all the battle cost the two armies nearly 14,000 casualties.

For Orders of Battle (regiments involved and brigade

casualties) to this battle, follow these links For more detail on this battle with photo's and the fight around the 35th Georgia sector, I strongly recommend the website "Battle of Fair Oaks" |